The world is in hell right now. Communal violence is high, wannabe dictators are Presidents and Prime Ministers, members of the LGBTQ community still have a tough time embracing their real identity in most countries, and hate speeches are openly made in public gatherings and political rallies as law enforcement agencies are compromised. With The Son of a Thousand Men/O Filho de Mil Homens, Daniel Rezende indicates that hate has always been present in our society. It's not a new disease. The movie, adapted from Valter Hugo Mãe's book of the same name, is set in the mid-twentieth century, and it doesn't look much different from our current reality. A grandfather tells a kid to stay away from "Sissies" and "Dykes." A woman with dwarfism is mocked by neighborhood ladies (they say that a man with "big heart" would destroy her organs). A mother considers killing her son because he is gay, "different," and "weak." And another mother narrows her daughter's path by forcing her to be a wife — that's all she knows, that's all she teaches her to be. It's evident that the mother herself is far from happy, yet she's so deeply conditioned by her own parents and so firmly embedded in the fabric of an orthodox society that she's unable to contemplate, let alone accept, new ideas about life.

Most characters, in fact, are as traditional-minded as that mother in the movie. They, however, serve as side characters, influencing the main action from the sidelines, like dangerous whispers trying to pollute the ears of the individuals at the center, who are the primary focus of this story. Someone like Francisca (Juliana Caldas) bravely fights idle gossip, though that doesn't mean she isn't occasionally wounded by idiotic remarks and the contemptuous gaze of her community. Then there is Isaura (Lívia Silva when young; Juliana Caldas when older), who, as a young girl, isn't able to stand up against her mother's backward thinking. Even Antonino (Antonio Haddad when young; Johnny Massaro when older) is forced by his mother, by society, to suppress his homosexuality. In a dreamlike sequence, he masturbates thinking of other boys, and those boys start attacking him. You must have heard about "butterflies in the stomach." Here, you see a room full of butterflies, which die along with Antonino's sexual fantasy.

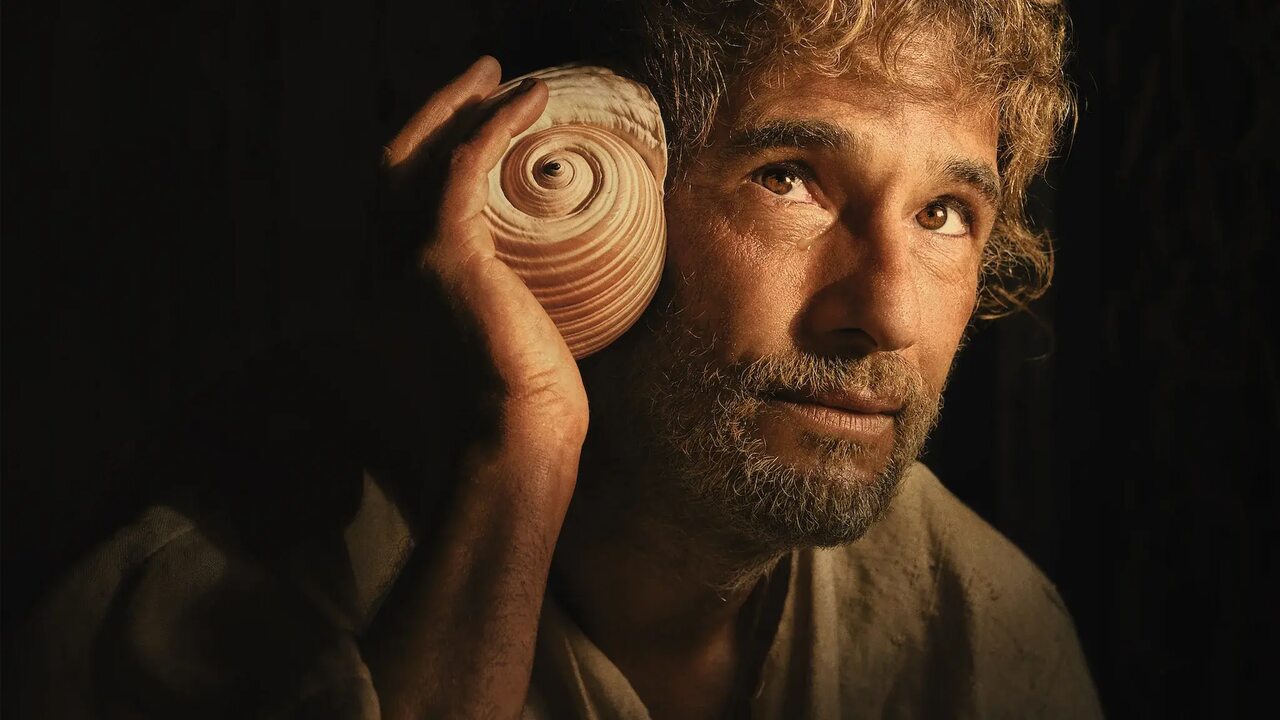

What Rezende wants to convey with this film is that hate isn't an incurable disease. Love is all you need to defeat it. To illustrate this point, we have a character, a young boy, Camilo (Miguel Martines), who stands in the middle of a bridge whose one side leads to conventional ideas and the other to progressive viewpoints. One part of Camilo is influenced by his grandfather's "wisdom," which dictates that "Sissies" and "Dykes" are enemies, while the other is in the process of learning liberal beliefs from Crisóstomo (Rodrigo Santoro), who is bathed in golden lights like a saint when he sees his newfound family holding each other tight. Crisóstomo, after all, means golden-mouthed, and his progressive views are the gold that comes out of his lips. If this name thingy sounds obvious, then wait till you watch the film. It's filled with obvious touches, obvious moments, obvious scenes. Rezende doesn't really go for "subtlety." He wants to create a poem with a "lyrical" aesthetic. The frames, however, look like picture postcards that are slowly fading. The images aren't expressive; they're purely decorative. They're tasty eye candy, just waiting to be screenshotted and used as desktop wallpapers or hung on a wall for vibes.

Rezende, by focusing more on the look of his film and dispensing the text like a moral lesson in plain sight, misses his characters' emotions and ends up giving you a slideshow of scenic beauty. The story earns our appreciation for its complex, interconnected threads that move between past and present, but this planning, too, feels like a mere embellishment — another ornament in a superficially attractive design. The Son of a Thousand Men, then, is the work of a decorator who looks at his adornments and smiles. Rezende's heart is in the right place—his intentions are earnest. That heart, however, is fallalery, and those intentions serve mainly as an excuse for the filmmaker to show off his photography.

Final Score- [4.5/10]

Reviewed by - Vikas Yadav

Follow @vikasonorous on Twitter

Publisher at Midgard Times

Get all latest content delivered to your email a few times a month.

Bringing Pop Culture News from Every Realm, Get All the Latest Movie, TV News, Reviews & Trailers

Got Any questions? Drop an email to [email protected]